Alle prese con Marta

Giorgio Zanchetti

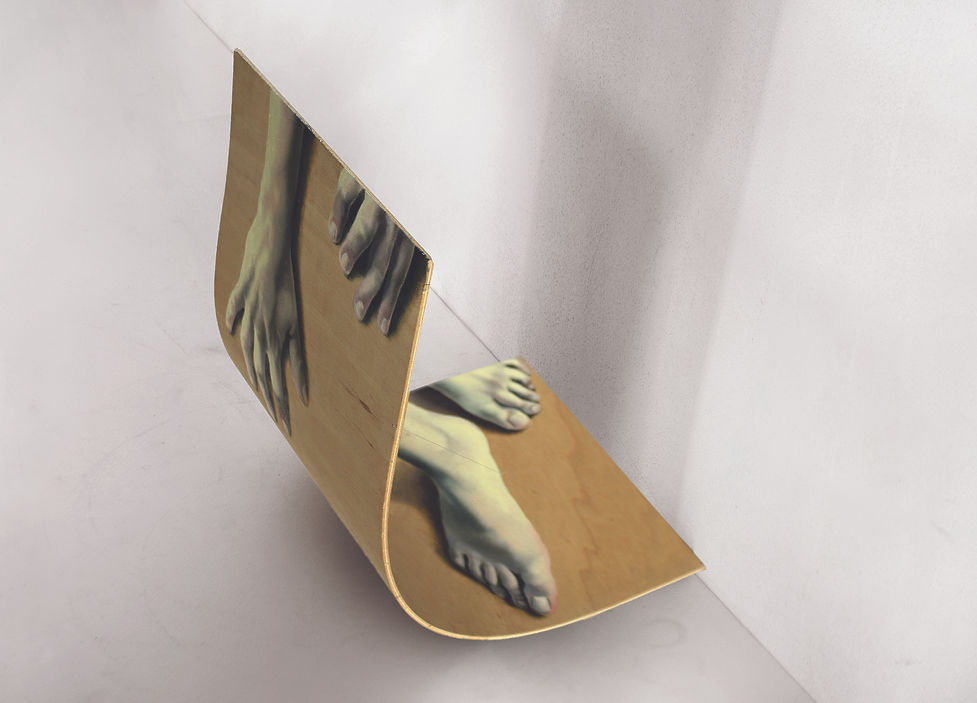

Di sale o di tabacco,di lotta e di governo, di potere, di forza o di potenza, di partito, di corrente, di servizio, di coscienza e di posizione, elettrica e d’aria, diretta, della colla, del gesso e del cemento, delle dita, dei denti e dei voti, in giro, in carico, in culo o per il culo, per i fondelli, per i capelli e per la gola…La giostra dei molti sensi possibili di ciascuna di queste Prese dipinte da Marta Dell’Angelo potrebbe compiacere e stordire chi provasse a guardarlesemplicemente come se fossero quadri, ovvero rappresentazioni pittoriche di membra, delle sue stesse membra, su una superficie bidimensionale. Il fatto di aver utilizzato la pittura, che parrebbe a prima vista giustificare l’inerzia dell’occhio, è una scelta di linguaggio precisa che vuole, al contrario, spingere oltre i suoi stessi limiti la nostra capacità di concepire il mondo attraverso lo sguardo. Sarei tentato di definire questa serie, iniziata nel 2020, come una prova di pittura concettuale, se con tale terminenon si corresse il rischio di incorrere, ormai, in un tecnicismo sterile, in questo contesto, e inutilmente limitativo. Mi piace allora chiamarla pittura mentale, accomunando in un’unica area semantica – forse un po’ nebulosa, ma proprio per questo corrispondente al brulicare delle stimolazioni estetiche di questi lavori – tutte le possibili transazioni tra il cervello e la punta del pennello: dallo stupore originario della mano che si avverte capace di autorappresentarsi, alle diverse gradazioni intellettuali del meraviglioso incarnate dallo scorcio, dal trompe-l’œil e dalla lanterna magica, fino all’immagine di un Marcel Duchamp come Testimone “oculista” (Oculist Witness), alle prese con un’idea del tutto teorica della pittura su vetro come procedimento all’inverso della pittura.Ma in concreto, intervenendo con le mani prima e poi con la loro rappresentazione dipinta a olio sulle tavole, sulle carte, sui vetri e sugli oggetti d’uso che ha scelto come supporti, Marta Dell’Angelo non vuole letteralmente “ingannare” l’occhio di chi guarda attraverso il gioco antico e nuovo dell’illusionismo, che sempre stempera tra il timor sacro e il riso, la metafisica alterità della pittura. Al contrario dimostra di voler celebrare ed espandere la capacità di vedere del nostro sistema occhio-mente, indicandoci entro la semplice regola materiale che si è prefissa – il dipingere a olio su una superficie – l’essenziale intreccio concettuale e sensoriale tra la rappresentazione e lo spazio ambientale, doveil dipinto e l’io che guarda si trovano a coesistere nello stesso tempo e con pari dignità. Il fatto che poi quelle membra che insistono sul supporto della pittura afferrandolo, misurandolo, piegandolo o deformandolo, ma anche semplicemente sfiorandolo o sorreggendolo, siano raffigurate solo per frammenti – che sono parti del corpo della pittrice fermato nell’atto quotidiano di prendere e manipolare nello studio i propri materiali – permette allospettatore di percepire fisicamente, quasi tattilmente, la qualità tridimensionale e relazionale dello spazio condiviso. Non si tratta dell’entusiasmo istintivo, primordiale o infantile per il riconoscimento del doppio: là dove c’era la sua mano sta ora la mano dipinta, un poco più grande per sembrare più vera e persino l’ombra portata, guarda, è dipinta! Sarebbe semplicemente il gioco usato degli uccelli di Zeusi, destinati a morire di fame per non aver saputo riconoscere un’immagine. Come scriveva a proposito della parola poetica Antonin Artaud: «un’espressione non vale due volte, non vive due volte; ogni parola pronunciata è morta, e non agisce che nel momento in cui viene pronunciata». Qui, invece, l’incommensurabilità reciproca tra realtà e rappresentazione è presa di petto fin dall’inizio e assunta coraggiosamente come punto di partenza per una diversa concezione dello spazio:ciascun particolare rappresenta, in assenza, la totalità di un corpo virtuale che ha agito sull’opera e adesso si pone, in essa, davanti al nostro corpo reale, mentre il confine tra pittura e scultura svanisce.Lungo quel margine dove il supporto materialmente finisce anche la rappresentazione del corpo dipinto fatalmente s’interrompe, lasciando idealmente il campo ad una rinnovata coscienza del reale. Perché il corpo non è l’argomento del dipinto, ma il dipinto stesso è il corpo. E quello che ho chiamato supporto (e che Dio sa come potremo tradurre in inglese) è il subjectile evocato ancora da Artaud, e ripreso da Derrida, cioè il supporto materiale dell’opera inteso a un tempo come presenza sensibile soggettiva e come oggetto fisico sul quale – o addirittura contro il quale – il pittore infligge l’atto della rappresentazione, contorcendolo concretamente o virtualmente fino a piegare o sfondare la sua coerenza bidimensionale interna, contraddicendo la sua intrinseca separatezza rispetto al mondo reale.Ma Marta Dell’Angelo non è il tipo d’artista che progetta le proprie opere per rispondere a una mia domanda, per dimostrare un teorema, per risolvere un problema o per corrispondere a una presa di posizione poetica scelta a priori. Certo non si sottrae a uno scambio dialettico volto a precisare il proprio fare e a collocarlo nel mondo in modo che sia comprensibile per gli altri (il testo di Vittorio Gallese pubblicato in questo stesso libro è frutto di un rapporto di reciproco interesse, nell’ambito di discipline diverse, che dura da anni). Però quello che tenta di dimostrare non va cercato al di fuori dei margini della superficie sulla quale si distende la rappresentazione, bensì al suo interno. La sua poetica non si aggiunge all’opera, ma ha sede nel corpo stesso dell’opera e dall’interno la motiva. Per Marta ogni lavoro è al tempo stesso domanda e risposta, o meglio il dinamismo di senso che scorre ciclicamente tra ogni risposta e una possibile nuova domanda. Per questo, quando le chiedo di ripetere a parole o di spiegare il gesto di una di queste sue mani dipinte, lei si sottrae alla domanda, parlandomi di altre mille cose, sfugge, non mi risponde e, scappando, con la mano indica il quadro. E se non ci credete, provate voi a prenderla.

Get to grips with Marta

Giorgio Zanchetti

Prese (grab, grasp) is a word that can be used inmany phrases and withdifferent meanings. Here are some example of its versatility:Presa di sale (a pinch of salt), di tabacco (a pinch of tobacco), di lotta e di governo (coup d'ètat), di potere (seizure of power), di forza, di potenza (power take-off)o d'atto (acknowledge), di partito (on principle), di corrente (socket), di servizio (take up service), di coscienza e di posizione (becoming aware and stance), elettrica e d'aria (plug and air vent), diretta (synchronized sound recording), della colla (glue setting), del gesso e del cemento (plaster and cement setting), delle dita (fingers grasp), dei denti e dei voti (teeth that grab and religious vows), in giro (teasing), in carico (taking charge), in culo o per il culo (to be trated unfairly or take the piss), per i fondelli (make fun of), per i capelli e per la gola (hair grabbing and taste buds tempting)…This carousel of the many possible meanings for each of these Prese painted by Marta Dell'Angelo could please and daze those who simply try to look at them as if they were paintings, or rather pictorial reproductions of limbs, her own, on a two-dimensional surface. The fact that she employs painting, which at a first sight may seem to justify the passivity of the eye, is a precise choice of medium which, on the contrary, wants to push our ability beyond its limit to conceive the world through the gaze. I would be tempted to define the series, which began in 2020, as a test in conceptual painting, if by using this term we would not incur the risk of using a sterile technical term and unnecessarily restrictive in this context. I like to call it mental painting then, combining in a single semantic area - perhaps a bit vague, but for this very reason it corresponds to the flood of aesthetic stimuli in these paintings - all the possible transactions between the brain and the tip of the brush: from the original amazement of the hand feeling capable of self-representation, to the different intellectual shades of the marvel embodied by the perspective, from the trompe-l’œil and the magic lantern, to the image of Marcel Duchamp as the Oculist Witness, dealing with a completely theoretical idea of painting on glass as a reverse painting process.In practice though, by working with her hands first and then representing them oil painted on boards, papers, glasses and materials she chose as canvases, Marta Dell'Angelo's intention is to not literally "deceive" the eye of the beholder by way of the ancient and new game of illusionism, always dissolving between sacred fear and laughter, that is painting metaphysical alterity.Conversely, Marta's intention is to celebrate and expand the ability of our mind's eye system to see, indicating us, within the simple material rule she set for herself - oil painting on a surface - the essential, conceptual and sensorial intertwining between representation and surrounding space, where the painting and the watching self coexist at the same time and with equal dignity. The fact that those painted limbs resting on the surface of the materials by grasping it, measuring it, bending it or deforming it, but also simply by touching it or supporting it, are depicted only in fragments - they are the painter's limb scaught in the daily act of handling and manipulating materials in the studio - it allows the observer to physically, almost tactfully, perceive the three-dimensional and relational quality of the shared space. It is not about the instinctive, primordial or childlike enthusiasm for the acknowledgement of the double: there, where her hand was, now there is the painted hand, slightly bigger to look more real, and even the shadow, look, it's painted! It would simply be the game of Zeusi where birds are destined to starve for not being able to recognise an image. As Antonin Artaud wrote about the poetic word: «an expression does not have the same value twice, does not live two lives; all words, once spoken, are dead and function only at the moment when they are uttered». Here instead, the mutual incommensurability between reality and representation is faced head on from the start and courageously taken as a starting point for a different conception of space: each detail represents the totality of a virtual body that has worked on the piece and now it places itself in it, in front of our real body, while the boundary between painting and sculpture vanishes.Along that margin, where the support materially ends, even the representation of the painted body fatally stops, ideally leaving the field to a renewed awareness of reality. Because the body is not the subject of the painting, but the painting itself is the body. And what I have called support above (God knows how we could translate it into English) it is the subjectile evoked, again, by Artaud and later by Derrida, that is, the material support of the painting (beneath the paint) intended at the same time as a subjective sensitive presence and as a physical object, on which - or even against which - the painter inflicts the act of representation, distorting it concretely or virtually to the point of bending or breaking its internal two-dimensional coherence, contradicting its intrinsic separateness from the real world.But Marta Dell'Angelo is not the type of artist who designs her works to answer my question, to prove a theorem, to solve a problem or to coincide with a poetic stance chosen a priori.Certainly she does not shy away from a dialectical exchange aimed at clarifying her work and placing it in the world in such a way that it is understandable for others (Vittorio Gallese's text published in this same book is the result of a relationship, based on their mutual interest in different disciplines, which has lasted for years).However, what Marta tries to demostrate should not be sought outside the edges of the surface on which the representation is laid out, but inside it. Her poetics is not an addition to the work, but it is placed in the body itself, in the work, and motivates it from the inside. For Marta every work is simultaneously question and answer, or better it is the dynamism of meaning that flows between each answer and a possible new question. Because of this, when I ask her to repeat in words or to explain the gesture of one of these painted hands, she shuns the question, talking to me about thousand other things, she escapes, she does not answer and runs away while pointing with her hand at the painting.And if you don't believe it, try to catch her yourself.

Quando prendere è comprendere. Performatività nell’Opera di Marta Dell’Angelo.

Vittorio Gallese

E’ con grande piacere e al tempo stesso con un certo pudore che mi accingo a scrivere queste poche righe in occasione della mostra Prese di Marta Dell’Angelo. Ho sempre pensato che uno dei punti di forza della creatività artistica consista proprio nella sua autosufficienza espressiva, che non ha bisogno di parole o spiegazioni. Ciò è forse ancora più vero se le parole provengono da chi come me è estraneo al mondo dell’arte, essendo impegnato da anni a tempo pieno nella ricerca neuroscientifica. Vi sono, tuttavia, degli aspetti dell’opera artistica di Marta Dell’Angelo che ormai da molti anni non solo giustificano, ma stimolano un possibile dialogo tra arte e scienza stimolato dalla sua opera. La ricerca artistica di Marta Dell’Angelo ha sempre messo al centro il corpo umano, declinandone in varie forme e con differenti media le molteplici potenzialità espressive. Le tecniche da lei praticate nel corso degli anni, come pittura, fotografia, video, performances, installazioni e la scrittura visiva di libri, condividono tutte un’unica caratteristica: esplorarel’universo del corpo umano, sondandone e sperimentandone le differenti potenzialità di senso. Il corpo umano studiato, interrogato e raffigurato da Marta Dell’Angelo ci interpella sulla nostra identità e sull’altro.Il corpo è sempre più centrale anche nella ricerca contemporanea delle neuroscienze. La nozione di ‘embodiment’, al centro del modello della cognizione umana come ‘incarnata’, implica che le parti del corpo, le azioni corporee o le rappresentazioni corporee svolgono un ruolo cruciale nella cognizione. La nostra natura biologica e le relazioni che intratteniamo col mondo grazie al nostro corpo determinano il modo in cui queste stesse relazioni sono modellate, regolate, e rappresentate. I neuroni e i circuiti cerebrali funzionano nel modo in cui funzionano solo perché sono collegati al corpo (Gallese, 2014, 2017; Gallese e Guerra, 2015). Cosa intendiamo esattamente quando parliamo di corpo? Il corpo rappresenta per noi la fonte principale della consapevolezza pre-riflessiva di sé e degli altri e la radice e la base su cui si sviluppa ogni forma di cognizione esplicita e linguisticamente mediata. Il corpo così concepito è l’a priori ultimo, la sorgente non ulteriormente riducibile della nostra esperienza. Come ci ha insegnato la tradizione fenomenologica, quando ci riferiamo al corpo, lo facciamo concependolo in una duplice veste e secondo due modalità, complementari e strettamente intrecciate: il corpo come Leib, cioè il corpo vivo dell’esperienza, e il corpo come Körper, il corpo materiale, studiato dalla fisiologia, di cui il cervello studiato dalle neuroscienze è parte integrante. Per questo motivo, quando parliamo di cervello dobbiamo sempre riferirci al cervello-corpo. Come è stato messo in luce da Merleau-Ponty (1945/2003), " io percepisco con il mio corpo"(p. 326), e " noi siamo nel mondo attraverso il nostro corpo e mentre percepiamo il mondo con il nostro corpo [...] percepiamo anche quello che facciamo con il nostro corpo, il corpo diventa un sé naturale e, in quanto tale, il soggetto della percezione"(ibid. p. 239). Conseguentemente, il corpo supera la divisione tra il fisico e il mentale "se noi introduciamo il corpo fenomenico accanto a quello oggettivo, se noi facciamo di esso un corpo soggetto di conoscenza "( ibid. p. 278).Questo catalogo e la mostra che illustra testimoniano un’ulteriore tappa della ricerca artistica di Marta Dell’Angelo sul tema del corpo, concentrandosi qui soprattutto sulla mano con la sua attività di presa sul mondo. La mano è stata a lungo al centro anche della mia ricerca neuroscientifica. Non possiamo comprendere chi siamo se prescindiamo dalla relazione con l’altro. In queste relazioni la mano gioca un ruolo da protagonista. Già prima della nascita, nelle fasi dello sviluppo della vita intrauterina, feti gemelli mostrano una peculiare motricità della mano che esplora il corpo dell’altro feto gemello con caratteristiche cinematiche diverse da quelle impiegate per esplorare le pareti dell’utero o il proprio corpo (Castiello et al. 2010).La mano, inoltre, è il fulcro della relazione tra gesto espressivo e linguaggio. Numerosi lavori scientifici hanno mostrato che parole e i gesti comunicativi eseguiti con la mano che condividono lo stesso significato si influenzano vicendevolmente, sia quando vengono prodotti che quando vengono osservati. Ad esempio, c’è un substrato neurale comune al meccanismo che consente di articolare la parola “ciao” e il meccanismo che consente di articolare il gesto della mano che ha lo stesso significato. Parola e gesto simbolico condividono uno stesso meccanismo cerebrale di controllo sensorimotorio. Ciò suggerisce che il linguaggio umano possa essersi evoluto più che dalle vocalizzazioni, dai gesti manuali di comunicazione sociale(per una rassegna, vedi Gallese 2008).Ulteriori studi di brain imaging hanno dimostrato che le stesse strutture corticali che controllano le azioni della mano si attivano anche quando ascoltiamo il rumore prodotto da azioni come bussare ad una porta, strappare un foglio di carta o applaudire. Inoltre, la lettura o l’ascolto di parole o frasi che descrivono azioni di mano attiva nel cervello di chi ascolta o legge i centri motori che controllano quelle stesse azioni. Anche se questi risultati sono ben lungi dal chiarire definitivamente come il nostro cervello-corpo costituisca e controlli la nostra competenza linguistica, essi sembrano indicare che al centro dell’intersoggettività umana, declinata come intercorporeità, vi siano meccanismi di simulazione incarnata, cioè il riuso delle stesse risorse neurali per eseguire azioni ed esprimere senso col corpo e per mapparli negli altri, anche quando tradotti in parole. L'architettura funzionale della simulazione incarnata è una caratteristica fondamentale del nostro cervello, che rende possibile la nostra ricca e diversificata esperienza dello spazio, degli oggetti e degli altri individui, ed è alla base della nostra capacità di empatizzare con loro. Come intuito dal Maurice Merleau-Ponty, dobbiamo considerare il gesto come linguaggio ed il linguaggio come gesto. Il naturale potere espressivo del corpo, di cui la mano è epifania quintessenziale, ci invita a cercare nel versante pre-linguistico l’origine di ogni senso. Le opere di Marta Dell’Angelo ci aiutano a comprenderlo senza bisogno di parole o esperimenti.Il nostro cervello-corpo si è evoluto nel corso di milioni di anni per interagire con un mondo fisico popolato da oggetti tridimensionali inanimati e altri corpi. La mano –che curiosamente è rappresentata accanto alla bocca nelle porzioni sensori-motorie del cervello, nonostante la loro non contiguità anatomica, quasi a tradirne la comune vocazione sociale e comunicativa – a un certo punto non si limita a costruire utensili, ma diviene costruttrice di simboli. La creatività simbolica, quella che a partire dalla modernità abbiamo imparato a riconoscere come produzione artistica, è la capacità di trasformare oggetti materiali conferendogli un significato che non avrebbero in natura di per sé, attraverso l’azione della mano. La mano creatrice di simboli da pragmatica si fa po(i)etica, permettendo di dare presenza, di produrre verità a partire dall’implicito sapere del corpo.Un aspetto rilevante per il nostro rapporto con l’arte riguarda la rivoluzione impressa al concetto di visione dalla ricerca neuroscientifica condotta negli ultimi decenni. Al netto degli aspetti interpretativi e di giudizio, legati al canone artistico, alla cultura e all’esperienza individuale di chi guarda, quando guardiamo un'opera d'arte, ciò che vediamo non è la semplice registrazione "visiva" nel nostro cervello di ciò che sta davanti ai nostri occhi, ma il risultato di una costruzione complessa, il cui esito è frutto del contributo fondamentale del nostro corpo con le sue potenzialità motorie, dei nostri sensi e delle nostre emozioni, della nostra immaginazione e dei nostri ricordi. Conosciamo e comprendiamo il nostro mondo, il nostro Umwelt, in virtù delle potenzialità relazionali istanziate dal nostro corpo, che a loro volta modellano e modellano gli schemi sensorimotori del cervello. L'obsoleto concetto oculocentrico di visione "puramente visiva" deveessere sostituito da un nuovo modello: la visione è un'esperienza complessa, intrinsecamente sinestetica, cioè fatta di attributi che superano ampiamente la mera trasposizione in coordinate visive di ciò che sperimentiamo ogni volta che posiamo gli occhi su qualcosa. L'espressione "posare gli occhi" tradisce, infatti, la qualità tattile della visione: i nostri occhi non sono solo strumenti ottici, ma sono anche una "mano" che tocca ed esplora il visibile, trasformandolo in qualcosa di visto da qualcuno.Il significato delle immagini non dipende, quindi, solo da concetti e proposizioni applicati alla loro registrazione ottica, ma anche da schemi sensorimotori, che mettono l’osservatore letteralmente in contatto con le immagini stesse, dando forma a una simulazione incarnata multimodale, che sfrutta tutte le potenzialità del nostro cervello-corpo.Le ‘prese’ di Marta Dell’Angelo testimoniano la qualità sinestesica e performativa della visione, sollecitando un’esplorazione delle immagini col proprio corpo, avvicinandosi, allontanandosi, girandogli intorno. La ricchezza di senso delle ‘prese’si rivela pienamente solo grazie ad una visione performativa che attraverso l’esplorazione attiva e dinamica, con il cambiamento di prospettiva e punto di vista dell’osservatore, rivela straordinari aspetti plasticidi tridimensionalità, potenziando la capacità della pittura di evocare il senso di presenza.Un ulteriore aspetto cross-disciplinare che mi viene spontaneo associare alle opere di Marta Dell’Angelo qui esposte riguarda il concetto di afferramento. La ricerca neuroscientifica ha rivelato che la nostra capacità di percepire ed immaginare le ‘prese’ si avvale degli stessi meccanismi neurali che presiedono all’esecuzione motoria dell’atto di afferrare. Percezione ed immaginazione sono, infatti, forme di simulazione: una simulazione mentale dell'azione che utilizza molti degli stessi circuiti cerebrali che sottendono l’esecuzione dell’atto di afferrare. Ciò vale anche quando leggiamo od ascoltiamo descrizioni linguistiche dell’atto di afferrare: quando leggiamo frasi come ‘Marta afferra la sedia’ nel nostro cervello si attivano parte degli stessi circuiti neurali attivi quando noi afferriamo fattualmente lo stesso oggetto. Ciò vale per tutti i verbi d’azione corporea. Ma ciò che rendela presa ancora più interessante è il suo uso linguistico per denotare un concetto apparentemente astratto e lontanissimo dal corpo: il concetto di capire qualcosa. In Italiano, infatti, ma anche in molte altre lingue come l’Inglese, il Francese o il Tedesco, si dice “afferrare un concetto” o “ho afferrato quello che hai detto”, intendendo con queste espressioni il significato di capire, comprendere (altro uso traslato dell’atto di afferrare). Questi esempi ci mostrano come anche gli aspetti più apparentemente astratti della nostra cognizione siano in realtà legati a filo doppio alla nostra natura corporea.Opere come ‘Strappi‘ rivelano un altro aspetto fondamentale della ricerca attuale di Marta Dell’Angelo: la capacità dell’arte di parlarci del rapporto tra ciò che a torto o ragione consideriamo reale e la sua rappresentazione, rapporto che qui appare in tutta l’indefinitezza e porosità dei suoi confini. La dipinta azione di strappo della carta che ricopre il reale contenitore per la pizza rivelandone la sottostante struttura trabecolare si fa interfaccia tra realtà e rappresentazione. E il quoziente di apparente realtà dell’azione dipinta viene amplificato spostando lo sguardo da una prospettiva frontale ad una laterale all’opera, che esalta la tridimensionalità della mano colta nell’azione. Questa porosità tra la realtà fisica e la sua rappresentazione, per inciso, appare in modo sempre più evidente anche dalla ricerca neuroscientifica: quando navighiamo nel mondo parallelo della finzione artistica, facciamo fondamentalmente affidamento sulle stesse risorse cerebrali e corporee modellate dal nostro rapporto con la realtà ordinaria. Queste risorse forniscono l'impalcatura funzionale e gli elementi costitutivi che il nostro coinvolgimento con le rappresentazioni di finzione riorganizza attraverso diverse forme di inquadramento.Le opere qui esposte ci presentano braccia e mani, colte nell’atto di afferrare oggetti, superfici, lastre di vetro, rendendo immediatamente visibile la connessione tra movimento, espressione e senso. Il sapiente uso di Marta Dell’Angelo del chiaroscuro e delle ombre conferisce profondità e presenza viva alla mano, la cui carnalità esce prepotentemente dalla superficie bidimensionale della tela, sollecitando in chi guarda una nuova consapevolezza della capacità espressiva del nostro corpo. Marta Dell’Angelo, grazie allo smontaggio del corpo, e alla ricontestualizzazione di sue parti in relazione al mondo degli oggetti, zoomando su mani e braccia plasticamente raffigurate e rimuovendo il contesto corporeo cui appartengono, le rende metonimicamente parte per il tutto, svelandoci la misteriosa complessità del senso del corpo,trasformando l’apparentemente banale atto motorio di afferrare oggetti e cosein un’epifania di presenza carnale.

Bibliografia

Castiello U, Becchio C, Zoia S, Nelini C, Sartori L, Blason L., D’Ottavio g., Bulgheroni M., and Gallese V. (2010) Wired to Be Social: The Ontogeny of Human Interaction. PLoS ONE 5(10): e13199.Gallese, V. (2008) Mirror neurons and the social nature of language: The neural exploitation hypothesis. . Social Neuroscience, 3: 317-333.Gallese, V. (2014). Bodily Selves in Relation: Embodied simulation as second-person perspective on intersubjectivity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014 Apr 28;369(1644):20130177.Gallese V. (2017). Visions of the body. Embodied simulation and aesthetic experience. Aisthesis, 1 (1): 41-50.Gallese V., Guerra M. (2015). Lo Schermo Empatico: Cinema e Neuroscienze. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore.Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945), Fenomenologia della percezione, tr.it Bompiani, Milano, 2003.

When Grasping is Understanding. Performativity in the Work of Marta Dell'Angelo.

Vittorio Gallese

It is with great pleasure and at the same time with a certain modesty that I am about to write these few lines on the occasion of Marta Dell'Angelo's exhibition Prese. I have always thought that one of the strengths of artistic creativity consists precisely in its expressive self-sufficiency, which needs no words or explanations. This is perhaps even more true if the words come from someone like me who is a stranger to the art world, having been engaged for years full-time in neuroscientific research. There are, however, aspects of Marta Dell'Angelo's artistic work that for many years now have not only justified but stimulated a possible dialogue between art and science. Marta Dell'Angelo's artistic research has always focused on the human body, declining in various forms and with different media its multiple expressive potentialities. The techniques she has practiced over the years, such as painting, photography, video, performances, installations and the visual writing of books, all share a single characteristic: exploring the universe of the human body, probing and experimenting with its different potentialities of meaning. The human body studied, questioned and depicted by Marta Dell'Angelo questions us about our identity and the other.The body is also increasingly central to contemporary neuroscience research. The notion of 'embodiment,' central to the model of human cognition as 'embodied,' implies that body parts, bodily actions, or bodily representations play a crucial role in cognition. Our biological nature and the relationships we have with the world through our bodies determine how these same relationships are shaped, regulated, and represented. Neurons and brain circuits function the way they do only because they are connected to the body (Gallese, 20114, 2017; Gallese and Guerra, 2020). What exactly do we mean when we talk about the body? For us, the body represents the main source of pre-reflective awareness of the self and of theothers and the root and basis on which all forms of explicit and linguistically mediated cognition are developed. The body thus conceived is the ultimate a priori, the no-further reducible source of our experience. As the phenomenological tradition has taught us, when we refer to the body, we do so by conceiving it in a dual guise and according to two modes, complementary and closely intertwined: the body as Leib, that is, the living body of experience, and the body as Körper, the material body, studied by physiology, of which the brain, studied by neuroscience, is an integral part. For this reason, when we talk about the brain we must always refer to the brain-body. Asithas been highlighted by Merleau-Ponty (1945/1962), "I perceive with my body"(p. 326), and "we are in the world through our body and while we perceive the world with our body [...] we also perceive what we do with our body, the body becomes a natural self and, as such, the subject of perception"(ibid. p. 239). Consequently, the body overcomes the division between the physical and the mental "if we introduce the phenomenal body alongside the objective body, if we make of it a subject body of knowledge" (ibid. p. 278).This catalog and the exhibition it illustrates testify to a further stage in Marta Dell'Angelo's artistic research on the theme of the body, focusing here especially on the hand with its grasping activity on the world. The hand has also long been at the center of my neuroscientific research. We cannot understand who we are if we prescind from the relationship with the other. In these relationships, the hand plays a leading role. Even before birth, in the developmental stages of intrauterine life, twin fetuses show a peculiar motility of the hand that explores the body of the other twin fetus with kinematic features different from those employed to explore the walls of the uterus or one's own body (Castiello et al. 2010). Moreover, the hand is at the heart of the relationship between expressive gesture and language. Numerous scientific work shave shown that words and communicative gestures performed with the hand that share the same meaning influence each other, both when they are produced and when they are observed. For example, there is a neural substrate common to the mechanism for articulating the word "hello" and the mechanism for articulating the hand gesture that has the same meaning. Word and symbolic gesture share the same brain mechanism of sensorimotor control. This suggests that human language may have evolved from hand gestures of social communication rather than vocalizations (for a review, see Gallese 2008).Further brain imaging studies have shown that the same cortical structures that control hand actions are also activated when we listen to the noise produced by actions such as knocking on a door, tearing a piece of paper, or clapping. In addition, reading or listening to words or phrases that describe hand actions activates in the brain of the listener or reader the motor centers that control those same actions. Although these findings are far from definitively clarifying how our brain-body constitutes and controls our linguistic competence, they seem to indicate that at the core of human intersubjectivity, declined as intercorporeality, there are mechanisms of embodied simulation, that is, the reuse of the same neural resources to perform actions and express meaning with the body and to map them in others, even when translated into words. The functional architecture of embodied simulation is a fundamental feature of our brains, which makes possible our rich and diverse experience of space, objects and other individuals, and underlies our ability to empathize with them. As intuited by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, we must consider gesture as language and language as gesture. The natural expressive power of the body, of which the hand is a quintessential epiphany, invites us to search the pre-linguistic side for the origin of all meaning. Marta Dell'Angelo's works help us to understand it without the need for words or experiments. Our brain-body has evolved over millions of years to interact with a physical world populated by inanimate three-dimensional objects and other bodies. The hand -which in the sensory-motor portions of the brain is curiously represented next to the mouth, despite their anatomical non-contiguity, as if betraying their common social and communicative vocation- at some point does not merely create tools, but becomes a creator of symbols. Symbolic creativity, the kind that since modernity we have come to recognize as artistic production, is the ability to transform material objects by giving them meaning that they would not have in nature per se, through the action of the hand. The symbol-creating hand from being pragmatic becomes po(i)ethical, allowing it to give presence, to produce truth from the implicit knowledge of the body.A relevant aspect to our relationship with art concerns the revolution imparted to the concept of vision by neuroscientific research conducted in recent decades. Net of the interpretative and judgmental aspects, linked to the artistic canon, culture and individual experience of the beholder, when we look at a work of art, what we see is not the simple "visual" registration in our brain of what is in front of our eyes, but the result of a complex construction, the outcome of which is the result of the fundamental contribution of our body with its motor potentialities, our senses and emotions, our imagination and our memories. We know and understand our world, our Umwelt, by virtue of the relational potentials instantiated by our bodies, which in turn shape and mold the sensorimotor patterns of the brain. The obsolete oculocentric concept of "purely visual" vision must be replaced by a new model: vision is a complex, inherently synaesthetic experience, that is, one made up of attributes that far exceed the mere transposition into visual coordinates of what we experience each time we lay our eyes on something. The expression "laying eyes on" betrays, in fact, the tactile quality of vision: our eyes are not only optical instruments, but are also a "hand" that touches and explores the visible, transforming it into something seen by someone. The meaning of images depends, therefore, not only on concepts and propositions applied to their optical registration, but also on sensorimotor schemes, which literally put the observer in touch with the images themselves, shaping a multimodal embodied simulation, which exploits the full potential of our brain-body. Marta Dell'Angelo's 'grasps' testify to the synaesthetic and performative quality of vision, soliciting an exploration of images with one's own body, getting closer, moving away, turning around. The richness of meaning of the 'grasps' is fully revealed only through a performative vision that through active and dynamic exploration, with the observer's changing perspective and point of view, reveals extraordinary plastic aspects of three-dimensionality, enhancing painting's ability to evoke a sense of presence.A further cross-disciplinary aspect that I feel compelled to associate with Marta Dell'Angelo's works exhibited here concerns the concept of grasping. Neuroscientific research has revealed that our ability to perceive and imagine 'grasping' makes use of the same neural mechanisms that preside over the motor execution of the act of grasping. Perception and imagination are, in fact, forms of simulation: a mental simulation of action that uses many of the same brain circuits that underlie the execution of the act of grasping. This is also true when we read or listen to linguistic descriptions of the act of grasping: when we read phrases such as 'Marta grasps the chair' in our brains, part of the same neural circuits that are active when we factually grasp the same object are activated. This is true for all verbs of bodily action. But what makes grasping even more interesting is its linguistic use to denote an apparently abstract concept far removed from the body: the concept of understanding something. In Italian, in fact, but also in many other languages such as English, French or German, we say "grasping a concept" or "I grasped what you said," meaning to understand, to comprehend (another translational use of the act of grasping). These examples show us how even the most seemingly abstract aspects of our cognition are actually tied in knots with our bodily nature.Works like 'Strappi' reveal another fundamental aspect of Marta Dell'Angelo's current research: the ability of art to speak to us about the relationship between what we wrongly or rightly consider real and its representation, a relationship that here appears in all the indefiniteness and porosity of its boundaries. The painted action of tearing the paper that covers the real pizza container revealing its underlying trabecular structure becomes an interface between reality and representation. And the apparent reality quotient of the painted action is amplified by shifting the gaze from a frontal to a lateral perspective of the work, which enhances the three-dimensionality of the hand caught in the action. This porosity between physical reality and its representation, incidentally, is also increasingly apparent from neuroscientific research: when we navigate the parallel world of artistic fiction, we basically rely on the same brain-body resources shaped by our relation to mundane reality. These resources provide the functional scaffolding and building blocks that our engagement with art fictional representations rearranges by means of different forms of framing.The works exhibited here present us with arms and hands, caught in the act of grasping objects, surfaces, glass plates, making the connection between movement, expression and meaning immediately visible. Marta Dell'Angelo's skillful use of chiaroscuro and shadows gives depth and a living presence to the hand, whose carnality emerges powerfully from the two-dimensional surface of the canvas, soliciting in the viewer a new awareness of our body's expressive capacity., Thanks to the disassembly of the body, and the recontextualization of its parts in relation to the world of objects, zooming in on hands and arms plastically depicted and removing the bodily context to which they belong, Marta Dell'Angelo makes those arms and arms metonymically part for the whole, revealing to us the mysterious complexity of the sense of the body, transforming the seemingly banal motor act of grasping objects and things into an epiphany of carnal presence.

Vittorio Gallese

References

Castiello U, Becchio C, Zoia S, Nelini C, Sartori L, Blason L., D’Ottavio g., Bulgheroni M., and Gallese V. (2010) Wired to Be Social: The Ontogeny of Human Interaction. PLoS ONE 5(10): e13199.Gallese, V. (2008) Mirror neurons and the social nature of language: The neural exploitation hypothesis. . Social Neuroscience, 3: 317-333.Gallese, V. (2014). Bodily Selves in Relation: Embodied simulation as second-person perspective on intersubjectivity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014 Apr 28;369(1644):20130177.Gallese V. (2017). Visions of the body. Embodied simulation and aesthetic experience. Aisthesis, 1 (1): 41-50.Gallese V., Guerra M. (2020).The Empathic Screen. Cinema and Neuroscience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945) Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).